One Who Will Be Ruler Over Israel (Micah 5)

No matter what you think about politics, it's been an interesting year. In the United States we've had one of the longest and most interesting presidential elections in years. And no matter what you think of the president-elect, you have to admit that expectations are pretty high for his presidency. In a congratulatory letter, French President Nicholas Sarkozy writes, "Your election raises in France, in Europe, and beyond throughout the world, immense hope." In fact, expectations are so high that the president-elect has tried to lower expectations, telling people that it's going to take time, that we need to think of the first thousand days of his presidency more than the first hundred days.

It's even been interesting in Canada. This past week, the Liberal Party of Canada will formally appoint its new leader. He has been called "the great Grit hope." A recent article said, "For many Liberals, qualities like this are a hopeful sign the party can rebuild after falling to a historic nadir in the Oct. 14 election. And for many Canadians, the 61-year-old Ignatieff is a statesman who could build the country's reputation on the world stage."

Not everybody is as excited about Obama or Ignatieff, but we have to admit that the phenomenon reveals something that is true of us as well. There is something within us that longs for a person of greatness to lead us. I realize that we're all cynical because we've been burned so many times, but there is something within us that longs for somebody to rise up and set things right, to inspire us, to give us hope, and to bring about – to borrow a tag line – change that we can believe in.

You even see this in movies. In Prince Caspian, a prince blows a magic horn, trying to summon help. The Narnians know they need help from Aslan or the Kings and Queens of Narnia. In Lord of the Rings, Aragorn is crowned King, heralding the new age of peace and the triumph of good over evil. And in the legend of King Arthur, the legendary British leader is buried beneath a tombstone that says, "Here lies Arthur, the once and future king." In other words, he's the former king, but he's also the future king that we hope for.

We want a king, a president, a prime minister, a leader, who can inspire us.

But worse than that, we're also angry at ourselves for wanting greatness for a leader. We want to believe, but we can't believe that we're falling for it again. So when the stock market crashes, layoffs are rampant, roads are crumbling, and debt and taxes are on their way up, we can't imagine that the next guy will be any better than the last guy, but we still keep on hoping.

So what do we make of all of this? Today I'd like to look at a passage of Scripture written 2,700 years ago at a time of crisis, and consider three things before we come to the communion table. One: why we're right to be cynical. Two: why, on the other hand, we're wrong to be cynical. Three: what this means for us this Christmas.

One: Let's look at why we're exactly right to be cynical about leaders.

Micah 5:1 says:

Marshal your troops now, city of troops,

for a siege is laid against us.

They will strike Israel's ruler

on the cheek with a rod.

In the decades before Micah wrote this, the Assyrian empire became a world power. The Assyrian empire was highly advanced in science. In fact, they were the first to divide hours and minutes into sixty, which has continued to today. It was a time of industry and knowledge.

Assyria became a superpower, and their armies swept through the Mediterranean seacoast. There was no stopping them. They were the first imperial empire in history, and ruled a vast area with a combination of careful organization and systemic brutality. Entire cities were destroyed, and their populations were either deported or massacred as examples to others. Their kings wrote of impaling and burning people, cutting off noses, ears, and fingers. You did not want the Assyrians attacking you.

But as we read verse 1, we discover that this is exactly the situation that they are facing in Jerusalem. A siege is being laid against the city, and we read that Micah calls them to "muster your troops." But it's not looking good at all, because Micah also predicts, "They will strike Israel's ruler on the cheek with a rod." This is humiliating and horrible news. The leader, the one who is supposed to deliver Israel, is instead defeated and humiliated. The current leader is weak and embarrassing. Micah does not predict good news. He predicts that the siege is going to end in defeat for Israel, and that Assyria will be victorious. Their salvation will not come from the hands of their own king.

So what actually happened? In 701 BC, the Assyrian army surrounded Jerusalem. They engaged in psychological warfare, getting the people to question their leader, and intimidating the people with their taunts. The residents of Jerusalem had every right to be scared, because the Assyrians had a pretty good win record. We read in 2 Chronicles that God did miraculously deliver Jerusalem from the Assyrian army, and that in a single night the angel of the Lord killed 185,000 Assyrians.

But we also read that just over a hundred years later, in 587 BC, Jerusalem fell after a 30-month siege. Because of famine in the city, resistance was pretty much non-existent. The king was blinded after being forced to watch his sons being killed. Jerusalem was captured and burned and its walls razed. Most of the population was deported and the remainder, mostly rural peasants, were left behind leaderless. The ruling line of David disappeared, and the temple was destroyed. Israel seemed ended forever.

So it's bad news for Jerusalem, and the leaders aren't going to be much of a help. In fact, the leaders are part of the problem. Earlier in Micah, at the start of chapter 3, the prophet gives a scathing rebuke to the leaders. He accuses them of abuse of power using some pretty graphic terms. The way the kings and leaders are treating their people is as brutal and damaging as cannibalism, he says.

What Micah is telling us is that, at least in his time, leaders had become corrupt. The temptations of power had gotten to them. Leaders often have this drive to succeed, to get ahead. This can easily lead to a lust for power, and ultimately to self-interest. Micah is clear that the solution to the crisis they faced was not going to be their leadership. And lest we think that we are better, we are not immune from the same temptations. It's why God warned Israel against even wanting a king. The prophet Saul warned Israel that they would one day regret wanting a king. "You will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the LORD will not answer you in that day" (1 Samuel 8:18). We want leaders, but they're never what we hoped they would be.

In fact, there's only one way to overcome the inherent weaknesses that we have as leaders and potential leaders: to own up to our shortcomings. Dan Allender says that the more we try to hide our weaknesses, the more controlling, insecure, and rigid we'll become. It will destroy us and damage those around us. It's only when we admit that we're so sinful that we will likely destroy everything we lead, that God begins to give us the grace that we desperately need.

Just to make it clear: our biggest problems are way too big for any leader to solve. Too big for any president, prime minister, party leader, pastor, or author. We need more than what any mere person can offer. But then Micah gives us hope, because there is a reason to hope.

Two: God will provide the king we long for.

He writes in verse 2:

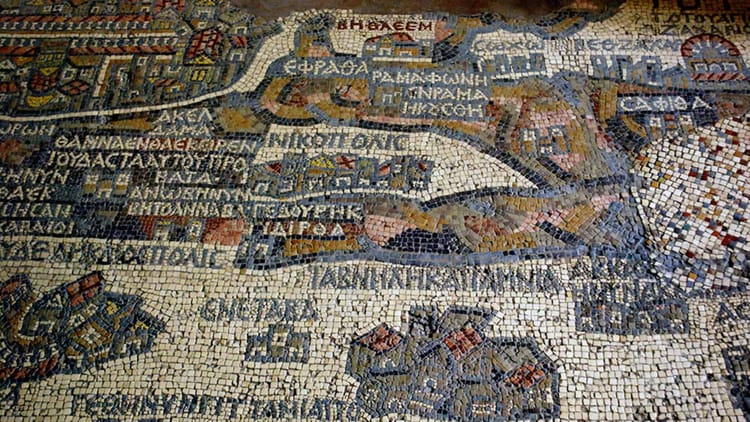

But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah,

though you are small among the clans of Judah,

out of you will come for me

one who will be ruler over Israel,

whose origins are from of old,

from ancient times.

Micah tells us that even though Jerusalem will be conquered, and even though the king will be struck on the cheek, a king will come who meets our deepest expectations and longings. And he will come from the most unlikely of places: not Jerusalem. You can't trust the kings who are born in Jerusalem, in the centers of power. These kings always failed. This king will come from Bethlehem, a town so insignificant that it's scarcely mentioned in the Hebrew Scriptures. But from the most insignificant place will come the most preeminent person, a ruler who is coming in the future, and yet is from of old, from ancient times. He is the once and future king.

This king will not come soon enough to help with the siege. Verse 3 says:

Therefore Israel will be abandoned

until the time when she who is in labor gives birth

and the rest of his brothers return

to join the Israelites.

But when he comes he will do more than even King David was able to do. Verse 4 says:

He will stand and shepherd his flock

in the strength of the LORD,

in the majesty of the name of the LORD his God.

And they will live securely, for then his greatness

will reach to the ends of the earth.

This is a king who will rule not just Israel. This is a king whose reign will reach to the ends of the earth. As the previous chapter tells us, nations will flow to Jerusalem, but not with armies.

Many nations will come and say,

"Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD,

to the house of the God of Jacob.

He will teach us his ways,

so that we may walk in his paths."

The law will go out from Zion,

the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.

(Micah 4:2)

This sounds, doesn't it, like the legends of a king who will set return and set things right: the Kings and Queens of Narnia, Aragorn, or King Arthur. J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings, and C.S. Lewis, author of the Narnia series, went out for a walk in Oxford one day near Magdalen College on a path named Addison's Walk. At this point, C.S. Lewis was not a Christian. They began to talk about the ancient legends. Are these ancient myths just stories, or do they express some deeper truths we hardly know how to express?

"But myths are lies, even though lies breathed through silver," said Lewis. "Myths are not lies," Tolkien countered. The myths we tell reflect a fragment of the true light. The story of Jesus Christ, Tolkien said, is much like the other myths, with one key difference: it really happened. Lewis came to realize that the story of Jesus is "the most important [story] and full of meaning." And soon afterward he became a Christian.

You see, all the other stories – of the return of the king, of the once and present king, of kings and queens who will return to vanquish foes and bring peace – all of these stories are echoes or shadows of the true story of Jesus Christ, with one difference: the story of Jesus actually happened.

In Matthew 2 we learn that this promised king is Jesus. Herod asked his scholars where the Messiah was to be born, and based on Micah they told him in Bethlehem. The king that Micah spoke of is the king we worship at Christmas.

What does this mean for us today?

It means that we have a lot in common with the people of Jerusalem in Micah's day. We are not under siege by a foreign army, mind you. But we have our problems: economic, political, medical, personal. We have car companies threatening bankruptcy, the Bank of Canada warning of severe economic turmoil, politicians being charged with corruption. At the same time we have movies becoming more popular. Movies are recession-proof, some are saying, because, as one person puts it, "it gives you an escape from all the stress."

We're longing for someone to provide the answers for these problems, or at least to get some relief from them. Micah tells us where to look for hope: not to our politicians, not to our economists, not to the movies (although you can enjoy your movies), but to a king who is born in the most unlikely of places, whose reign is from old, and who shall be great to the ends of the earth, and will be their peace.

Just as the people under siege longed for this king to come, so we long for this King to reign. We're longing for the story to unfold of which all the other stories are only a shadow. The new heavens and new Earth are coming in which "everything sad is going to come untrue."

It also takes the pressure off of us. Martin Luther was friends with Philip Melanchton. Melanchton would occasionally worry a bit too much, one time in particular about the situation in Germany. Luther chided him, saying, "Let Philip cease to rule the world." We don't need to worry. Luther explained, "It is none of our work to steer the course of providence, or direct its motions, but to submit quietly to Him who does." There is a king who reigns, and that king is not us.

Most of all, this points us to Jesus, the most unlikely of kings who came from the most insignificant of places. Micah said that he would" shepherd his flock in the strength of the LORD." Jesus said that he is the shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep. It's only the most unlikely of kings who would die for his people, but this is the king who will reign. When we see Jesus as the true king that all the other stories point to, we can say with C.S. Lewis, "I have just passed from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ."

We thank you today for the king born in the most insignificant of places, a ruler whose from old, from ancient days. We thank you that he will shepherd his flock in the strength of the Lord; that he will be great to the ends of the earth; and that he shall be their peace.

We long for this once and future king, and so we pray, "Even so, come Lord Jesus. Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven."

And we come to his table now as we look back on his death for us, and as we look forward to his reign over all the earth. In Jesus' name, Amen.